NO, CRASS haven’t just gone disco. They went disco years ago.

What, precisely, Crass were trying to do when they released Walls on their first proper album Stations of the Crass remains unclear, even 42 years later.

Maybe it was one of their famous pranks that didn’t come off.

As one YouTuber comments:

“This is such a bizarre song, by Crass standards, but so brilliant. It is great to dance to, that bass line is filthy when audible, honestly they should have done a 12-inch extended version of this that went on for 10 to 12 minutes.”

Ten to 12 minutes at the very least.

Either way, what is clear is that the wobbly, bass-heavy groove that accompanies Joy de Vivre’s falsetto vocal, probably owing more to PiL or ESG than it does Chic or Earth Wind & Fire, makes Walls sound like nothing else in a hugely diverse back catalogue.

Well, it sounded like nothing else in their back catalogue until very recently.

Towards the end of 2019, the stems for the individual elements of each track on the first Crass release, The Feeding of the 5000 were made available as a free download from One Little Independent Records.

According to OLI’s website, the intent was for “people to create their own remixes and interpretations and breathe fresh life and ideas into this revolutionary music. Crass encouraged people to rip apart the sound and ideas and create something new, then send the files to Crass Records for future releases and charitable projects. The message is DIY like it never was before.”

“Yours for the taking, yours for the making,” continued Crass, apparently. “You do it, we’ll stew it. Mix it backwards, forwards, and upside down. Turn up the heat and fix it with a downbeat, bring in the trumpets and let ‘em blow, let the piper call the tune to let us all know, it’s up to you to do what you like with it.

“The only limitation is your imagination.”

Actually, I can imagine Penny Rimbaud saying this.

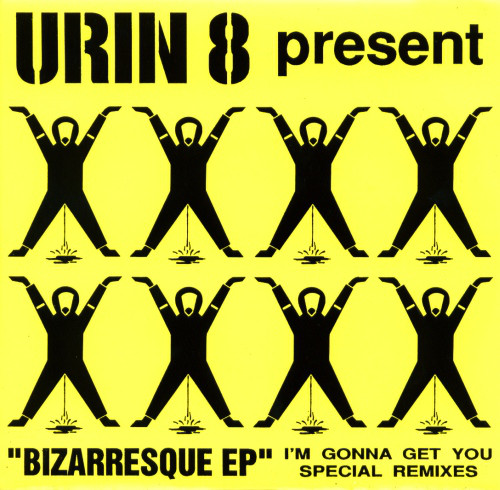

The idea seems to be to release some kind of Bullshit Detector-like compilations but, in the meantime, OLI has paired dancefloor-orientated cuts by the likes of EDM cake enthusiast Steve Aoki and XL Recordings boss (and half of vintage rave act Kicks Like a Mule) Richard Russell with more leftfield interpretations from people such as Paul Jamrozy of Test Dept and longtime Eve Libertine collaborator Charles Webber.

These remixes have been released as a series of limited edition 12-inch EPs under the name Normal Never Was, with all monies raised donated to Refuge – a UK charity providing life-saving and life-changing services for women and children who have experienced domestic violence and abuse.

Responding to the release of these remixes, one unimpressed older fan, posting on the mostly wonderful Crass Facebook page, described the project as “Crass go disco”.

Funny, but as I think we have established, Crass went disco years ago.

And what’s wrong with disco anyway?

THE SHOCK OF THE NEW

THANKS to a combination of word of mouth, fanzine and music press coverage, and the patronage of the Blessed John Peel, once Crass began releasing records in 1978, they quickly went viral. The stark, angry, apocalyptic music they produced, it seemed, was perfectly in tune with the times.

A united kingdom in name only, at the end of the 70s Great Britain and Northern Ireland was, in today’s parlance, a total fucking shit show. Widespread unemployment, rampant inflation, unrepentant racism, misogyny, homophobia, ignorance and corruption combined to create an ugly, oppressive, stifling atmosphere of everyday menace.

Aki Nawaz was brought up in a traditional but fairly liberal Pakistani family in Bradford – and although he’s talking about his hometown, he could easily be referring to any number of places in the UK at the time, particularly in the big cities and the north of England:

“We grew up in a very diverse community,” says Aki. “There were natives, Polish, Italians, Afro-Caribbean and Chinese. That brought its own conflicts but it also brought liberation. You heard different languages and heard about different experiences.”

“There was British culture, Yorkshire culture, Pakistani culture, Muslim culture, all the other cultures that you get in Bradford. They were really tough times, there was racism all over the place. It was oppressive but it was also liberating. It was interesting.

“When you wake up in a morning, you’re one person before you go to school, you’re another person at school, you come back, you’re a different person,” says Aki of the hoops the children of immigrants had to jump through at the time.

“Then you spend some time with your family and you’re a different person, and then you go out with your mates, up to some mischief or playing sport, and you’re a different person.”

“So there were like all this playing out every day, in terms of language and culture and food. And there was the Yorkshire thing too. Billy Liar meets, I dunno, Ravi Shankar.”

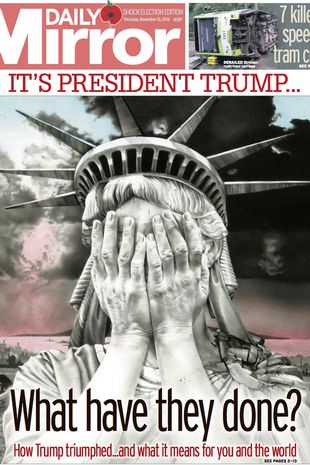

And then Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative party won the 1979 General Election.

Before she began her political career, Thatcher’s contribution to science was to (supposedly) invent a way of injecting air into ice cream to bulk it up without adding actual ingredients that would have cost money.

Later, as education secretary, she decided to save the state a bit of cash by removing the right to free school milk for younger school kids. If parents wanted their kids to drink milk, it was their responsibility to provide it.

Thatcher adopted the monetarist model of capitalism, where direct taxes on salaries are reduced and indirect taxes on ‘luxuries’ like fags and booze are increased. Despite supposedly being against the principle of big government, the Thatcher government raised interest rates to limit the amount of money in the economy and reduce inflation – which did eventually happen but at the cost of crippling anyone who happened to be in debt.

State-owned monopolies were bad, it seemed, and free market competition was good. Financial services were to be deregulated and state-owned assets – British Rail, British Steel, British Telecom – sold off to the highest bidder. Powerful trade unions that fought for their members’ interests were not part of the equation.

For anyone unaware of just how much of a crank she was, Thatcher’s genuinely unnerving victory speech on the doorstep of Number 10, like an unblinking Norman Bates in his mum’s twinset and pearls quoting the Prayer of St Francis, makes it disturbingly obvious:

“Where there is discord, may we bring harmony, Where there is error, may we bring truth, Where there is doubt, may we bring faith, And where there is despair, may we bring hope.”

The irony is, the utterly cynical bullshit that Thatcher spouted that morning could almost serve as a manifesto for Crass themselves.

Apart from the harmony bit, obviously.

Either way, the battle lines were well and truly drawn.

“I thought I was a punk, and I was listening to the UK Subs, people like that,” says Mark Goodall of his early years in North Yorkshire. “I was still living at home, and I ordered the Feeding of the 5000 from a Small Wonder mail order ad in the back of Sounds.”

“And when it came, first of all, the first track wasn’t on it. You know, because the people at the pressing plant had refused to press Reality Asylum. So there was this silence.

“I had to listen to it with my headphones on in my room, because I didn’t want my parents to hear it, and the needle seemed to go around this groove for ages. I thought, there’s nothing here. And then the first track after that is Do They Owe Us a Living. So that comes in and you just think, shit! It was so uncompromising.

“And you’re doing that thing where you’re listening to an album by the Beatles, or Wings, and you’re reading the lyrics – except it’s Crass and they’re using all the language that you weren’t allowed to use. The subject matter, for a teenager, was just mind blowing.”

“A friend of mine bought Reality Asylum and we were pretty shocked to be honest with you,” says Chris Liberator. “I’d seen punk on the telly, saw Mark Perry talking about how earlier music had got to go, I bought Peaches when it came out.”

“I was only 13. Reality Asylum just totally rocked my world. I just got into independent music completely, listening to John Peel every night, buying Desperate Bicycles records, all that kind of stuff.

“But Reality Asylum really did knock me for six. I remember my friend saying he’d got this record and it was 45p and it’s really brilliant and you need to read all the anti-religion stuff on the sleeve. It was shocking for me because I’d be brought up in a religious house – well, not really religious but religious enough for me to be shocked by it.

“It was a big moment for me.”

“I got into punk, like a lot of people my age, in the 70s when I heard Never Mind the Bollocks,” says Matt Grimes. “The things that attracted me was that I immediately knew it was something that would upset my parents. It was the perfect excuse to get into it.”

“I grew up in a household where there was always music, so I was always into it. Punk rock just seemed to speak to me in many ways. It didn’t take me long to move on from what, with hindsight, seems like that very commodified, mainstream punk, to stuff like Crass.

“I remember being turned onto Crass by another punk who was a year older than me. First time I heard Feeding, I just thought, well that’s a load of fucking rubbish. But I persevered with it until I got it. I think the thing that really cemented it for me were the lyrics – and Crass were kind enough to provide lyric sheets with their albums.

“I used to spend hours listening to it – really, the music was almost in the background, secondary to what you were reading. I remember reading this stuff and thinking, this absolutely articulates the things that I don’t have the language to articulate. I would have been 15.”

Dev Jonlin grew up in Beeston, close to Elland Road in south Leeds. He says he was not long out of his altar boys clothes when the first Crass single was released.

“I’d been getting into punk and seen a few bands live but this record threw me sidewards,” says Dev.

“At the time, Reality Asylum wasn’t punk. I played it just once and instantly sent it to the weird section. I remember hearing Shaved Women and absolutely shitting myself. It was the train sound, the repetitive ‘screaming babies’, the jagged guitar. There was no verse and chorus and singalong bits like on the Clash’s first LP.”

Dev says that he had the definite feeling that he was stepping out of the normal and everyday.

“More than anything I thought what am I getting into? I know punk was all new to me and a whole world of discovery but this felt evil and that I was getting drawn into some sort of a cult.”

Everything changed for Aki Nawaz one day in 1977 when he came home from school to find his brother had bought the first Clash album.

“I put it on and it was almost like the Bible being read to me, y’know, I’d gone up to see the burning bush,” he remembers. “God had spoken to me through punk.”

“I never had any money to buy records. And I don’t know how my brother managed to buy them because he never had any money either.

“The day after, I went to school, I spiked my hair up and I had a baby’s dummy stuck onto a really bad waistcoat.”

Aki ended up having to sneak his clothes out the house when his parents weren’t looking.

“But by then, the community already knew that I was just a lost cause,” he says. “It wasn’t even like they were saying, oh he’s rebelling, it was like, he’s having a mental breakdown. They didn’t see it as rebellion, they just thought, he must be taking drugs, he must be drinking. Look at the state of him. He’s a tramp. So there’d be all that narrative running.”

The first gig Aki ever went to was the Sex Pistols when they played in Keighley later that year.

“It was at a club called Knickers. It was a strip club wasn’t it? We got there earlier in the day and tried to get in for free but we never managed. We got in just after the soundcheck and I remember Sid Vicious walked out and he’s like pretending to be drunk, or he was drunk. But yeah, it was a great gig.

“But then we’d go home and it was late and my dad would say, where have you been? Look at the state of you, and all that shit, and we’d say, dad, we went to see Star Wars. What? At one o’clock in the morning? Well, yeah, we went to see Star Wars and then we saw uncle Choudhury – we’d just make up somebody’s name – and he wanted to talk about you.

“Y’know, we were completely and utterly lying through all them years.

“Bless him. My dad was a lovely guy but he was like just a broken man because both me and my brother got into punk.”

Aki threw himself into the burgeoning Yorkshire punk scene, seeing just about everyone on the circuit – including the Clash, PiL, Joy Division, the Banshees, Penetration, the Ants, Wire, the Drones, 999 and the Angelic Upstarts.

Aki, his brother and their fellow Bradford punks would pile into Aki’s dad’s car and go anywhere that wasn’t Bradford – London, Manchester, Newcastle, it didn’t matter. Aki, it seems, was the permanent designated driver.

“I’ve never drunk alcohol,” he explains. “And I never took any drugs in all this madness that’s going on around me, people taking whatever they wanted to take, sniffing glue, y’know, doing Zof – that stuff that you use when you’ve had a plaster on? Everybody was at it. I was almost like the carer of the Bradford punks.”

“And then we’d get into trouble, or get into fights, or I’d get picked on because I was the only Asian or the only black guy or whatever. It’d get really heavy. You’d have to run out of places. Leeds was very dangerous at that time. The skinheads were very violent there.

“But punk was like a new religion for me. And we were around a lot of old hippies and bikers so we were getting like a mature advice on how to rebel even more.”

A few of Aki’s mates, and a kid called Chris Boredom in particular, “were very into anarchy” and introduced him to the music of Crass.

Previously, all he knew about Crass was that they were “really loud and brash”, but once he heard their records and saw their artwork and record sleeves, he began to understand “they were pushing the envelope of punk, probably to what it should have really been all along.”

“Punk had already started to sell out,” he says. “The contradictions and the hypocrisy of punk had already begun by then. On one hand they were saying, we’re anti system, we’re anti this, we’re anti that. And they’re all on major labels. But Crass gave us something that was a bit more honest in terms of philosophy.”

“As far as Crass were concerned, they didn’t even think the Pistols were real punks. I just thought they were fresh. They weren’t following anything. They were unique.”

“I got into stuff like the Sex Pistols when I was about 11 or 12,” says Brendan Hodges. “The Clash, Buzzcocks, X-Ray Spex, all that kind of stuff. I read an article about Crass in the NME in the school library, and it was the most scurrilous blasphemy – this was around the time when Life of Brian came out. That just did it for me, I was like, I’ve got to find this band.”

“I couldn’t find anything locally, and then I went to Portsmouth and got a copy of Bloody Revolutions when it came out. I listened to it and that just blew my mind.”

David Oliver, stuck in the middle of nowhere in Wiltshire, first heard the early punk stuff on John Peel’s week-nights radio show. One of his friends bought Smash it Up by the Damned when it came out “and then we just started going around smashing things up in the town, spray painting and glue sniffing and whatever you do when you’re a young punk.”

“And then suddenly the Crass thing fell on us, at some stage, after the real punk thing. They were pretty scary, because their lyrics were so different to the Damned or the Stranglers or PIL, you know. It was a total sort of reality wake up.”

Mark McKenzie – everyone calls him Choci – is a Londoner by birth but grew up in Cambridgeshire. Although Choci missed out on the Pistols, he was really into bands like Stiff Little Fingers, the Ruts, the Damned and the Ants “before they became popular” at a “proper young” age.

“Punk rock was very angry. Fuck the system. Never trust a hippy. It was there to shock. You had the swastikas, upside down crosses, Seditionaries bondage. My mum came in one night and I was sticking a safety pin through my nose.”

“I used to have Wasted Youth painted on the back of this raincoat and I remember one day in Cambridge this old lady came up and gave me a fiver and said, it’s okay mate, you’ll be fine, you’ll find a direction in life. I was like, thanks!”

Choci first came across Crass at Andy’s Records in Cambridge.

“We used to travel into town on a Saturday morning and flick through the singles,” he says, although the first Crass record he actually bought was Stations of the Crass.

“The cover was this big fold out thing, like this big collage. I’ve still got it. As a young impressionable, it was quite the thing. It was quite left of the field. And they all wore black and were quite faceless. And then I put it on and I was like, yeah. Wow!

“There was the whole political content. You could feel the anger. You could feel the passion and drive, the dislike of authority and imperialism and colonialism. And war. And I was like, yeah, I’m aligning with this. This is cool.

“It was kind of a hippy vibe. The hippies were all like ‘Make love not war’ and Crass talked about ‘Fight war not wars’. There are similarities there. It’s almost like Crass were hippy punks. They’d taken this political ideology from the hippies but instead of promoting it with flowers and acid it was all speed and Tuinol and fucking having it.”

While it’s an entertaining notion, it wasn’t quite speed and Tuinol and fucking having it for everyone in those days. Paul Hartnoll, for example, was a music-loving 10-year-old in Dunton Green near Sevenoaks in Kent when he first saw punk rock on TV:

“I absolutely loved the whole Sex Pistols thing,” he says. “I liked the anti-establishment and anti-parent swagger they had. Everything that came out of their mouths upset adults and I just thought that was brilliant.”

The first musical movement that Paul was truly able to feel a part of, however, was 2Tone.

“When I first heard the Specials and Madness, I went mental. I literally went from playing with Action Men and toy soldiers to wanting to dress smart and be a bit of a lad when I heard 2Tone. It was like, there you go – that’s the way forward.”

“And when 2Tone kind of fizzled out, that whole second generation of punk, the more boisterous stuff, the Exploited, Anti-Nowhere League, Vice Squad came along and I got into all of that,” he says.

Paul listened to John Peel, tentatively it seems, but never heard Crass.

“John Peel used to be a bit scary though. I listened to him when I was younger and it was always like, right, is this going to scare me or is it going to interest me? But I also remember hearing Blue Monday on John Peel and thinking, that’s weird. I’ve never heard a drum do that before.”

Paul’s introduction to Crass came in 1982 through a mate that he only saw in the summer, when their families would holiday in their caravans on the same camp site in Hastings. He was, says Paul, a real connoisseur of punk, and having told him what he was into since the last time they saw each other, he was informed:

“No, no, no, no. You’ve got to listen to Crass. So I used to carry a tape recorder around all the time and he had tapes. He played me Bloody Revolutions. And I just went, FUCK.”

“Okay. I’m in. Brilliant.

“And from there I went onto Tube Disasters by Flux of Pink Indians and it just blew my head off,” he adds. “It wasn’t just the music – although the music was brilliant – but it was the fact they were properly saying something and making sure that you could hear what they were saying. And all the lyrics were printed out. It was almost like an instruction manual for life.”

Not everyone got Crass. Harry Harrison was introduced to the band by his friend Pete Birch in their home town of Bolton, also at some point in 1982.

“I’d seen Crass on the back of people’s jackets,” remembers Harry. “I met Pete when I was 15 and he introduced me to loads of stuff, including Crass – who we both hated musically.”

“But I had a mate called Whitey who lived in Bromley Cross and went on to drum for the Electro Hippies, and he went to stay with Crass in the New Forest or wherever they live.

“He was a bit older than us, he was 17, this supercool Bolton punk with his own car – if you can imagine such a thing. So, he was into Killing Joke and I got more into them.

“I was already into the Damned, like classic punk rock, and the American hardcore thing, and a bit later, Sonic Youth, Butthole Surfers, Fugazi. But what I really loved was the Mob.

“I liked a bit of Zounds. But the Mob, and Let the Tribe Increase, that album. And Chumbawamba. I’ve always liked a tune, to be honest.

“Crass, musically, just never did it for me at all. Politically, I thought it was fantastic. I got the whole thing. I just didn’t like the music.”

Having seen the new punk phenomenon on TV, Alice Nutter found some records in a phone box on Burnley bus station, including a copy of God Save the Queen, only for her dad to smash it to pieces when she took it home and played it.

Crass were another thing again.

“I was utterly freaked out. Is it Stations of the Crass that the Myra Hindley song’s on? What happened is, I played it at the wrong speed. It was an album but you had to play it at 45 – and I didn’t know. So I played it at 33 and I was listening to that Myra Hindley song in my bedroom, and I thought, these people are evil.

“Honestly, I had my hands over my ears, going, these are very sick people.”

“It really upset me. And it was only when I said to somebody, they’re fucking weird, and they were like, what are you talking about? You’ve got it on at the wrong speed!

“When I actually unfolded the sleeve, I’d never seen anything like it. I’d never seen anything like all those words on that kind of paper, in black and white. And those images.

“Obviously, I had lots of albums, but the punk albums I’d had before that were more day-glo. Like Give ‘Em Enough Rope was completely colourful and bright. It looked like an album. You didn’t look at it and think, what the fuck is that? I opened up that Crass album, honestly, and I’d never seen anything like it.

“And then you had to work out how to fold it up again. It were like, what is this weird thing?”

SHAVED WOMEN, DISCO DANCING

THE MUSIC that Crass made was never quite as monochrome as their seemingly fold-resistant record sleeves might have you believe.

While their music was strictly utilitarian in that it only existed to provide a platform from which they could deliver ideas, the collision of changing abilities, attitudes and perspectives within the band meant that their music continually evolved and mutated throughout their self-imposed seven-year lifespan.

“It was an interesting band because of that mixture of characters,” says Mark Goodall. “It’s rare that you get some old hippie, some seriously feminist singers, a punk singer – like a Johnny Rotten character, Steve Ignorant – and you get this weird collective, which I think might be the key to why they were so different.”

It’s a good point. As well as their trademark blam-blam-blam punk rock – which got more and more extreme the closer they got to 1984 – the Crass back catalogue also contains inventive and sophisticated post-punk jams, elaborate musical parodies and pastiches, and evocative audio collages with cut up and transposed found sounds.

There were snatches of TV ads, Women’s Hour and public information films – all accompanied by righteously indignant monologues by one of the band’s four singers.

They even found time to produce sequenced, seaside organ-style reinterpretations of their greatest hits for family Christmas get-togethers. I mean, can you imagine?

All this, and contemporary classical music too. It’s quite the body of work.

Similarly, for every Conflict, Anthrax or DIRT banging out rabble-rousing, loud, fast and, let’s be honest, strictly by-the-numbers, rough and ready street punk on the Crass label, there were more acts releasing genuinely inventive, innovative and uncompromising leftfield music.

Let’s hear it for the utterly transcendental Rudimentary Peni, the Mob and the Poison Girls, the Cravats, the Snipers and Flux – not to mention such wayward talents as Annie Anxiety Bandez, Andy T, D&V, KUKL, Sleeping Dogs and Hit Parade.

The label even put out something approaching pop music with releases by Zounds, Omega Tribe, Captain Sensible and the label’s first signing, Honey Bane.

There were also a number of top-quality bands that first appeared on the three Bullshit Detector compilations, including Chumbawamba, Passion Killers, Napalm Death, the Sinyx, Naked, XS, Kronstadt Uprising, Metro Youth, Destructors, Riot Squad and APF Brigade.

That is what you call a roster. But music for dancing? Not so much.

In Crassland, remember, not only are the ‘Shaved women shooting dope’, they are also ‘disco dancing’.

What next? Shaved women popping pills?

In the anarcho scene, ‘disco’ became shorthand for anything mainstream, soulless and inauthentic – not a million miles away from the tired tropes trotted out by the racists and homophobes who supported the ugly-as-sin ‘Disco sucks’ campaign in the US in 1979.

But we had different prejudices over here. The demo that won Amebix a place on Bullshit Detector 1 included a 12-minute jam called Disco Slag that sounds very much like ESG having an argument with the Butthole Surfers in some shithole squat in Bristol – but not in a good way.

You can see why a different track – ironically enough, the wonky tribal yob funk of University Challenged – ended up on the compilation.

A few years later, Flowers in the Dustbin somehow ended up playing in some glitzy club in the Midlands and felt so alienated by the experience they called their debut EP Freaks Run Wild in the Disco.

‘Interestingly’, when Merry Crassmas was released in 1981, the Dutch production act Starsound aka Stars on 45 (led by a former member of Golden Earring, no shit) were doing well in the charts with mind-numbingly banal medleys of sequenced pop hits, an idea they ripped off from sequenced disco records that were designed to allow DJs to take extended bathroom breaks – although the first person to string different songs together in one extended sequence (both on vinyl and live) was Hansi Last, probably.

We can only guess why Crass didn’t do at Stars on 45-style Crass on 45 with a stupid ‘disco beat’ underneath their greatest hits – they loved being different from everyone else, the little scamps – but I think it would have been much funnier if they had.

Either way, disco, it seemed, was not for us.

Crass punk wasn’t music for dancing, although Zounds, Crass and Poison Girls occasionally produced a strange kind of edgy punk funk – tracks like Subvert, Nagasaki Nightmare and Reality Attack have definitely got a groove.

But there wasn’t much room for subtlety in the moves you could pull at Crass gigs, which were usually at full capacity (if not beyond it).

It was generally just a case of pogo-a-go-go.

Plus, all too often, the crowd contained right-wing nutjobs intent on mayhem. For many of us, Crass gigs didn’t exactly feel like the kind of places where you could relax and get your groove on.

And, of course, they weren’t meant to be. Crass gigs had a different purpose entirely.

“The first Crass gig I went to,” says Sid Truelove, “they played an intro tape that was a mix of these suddenly very violent sounds, and they had screens with like film of abattoirs. It was an audio visual nightmare.”

“And I thought, fucking brilliant.”

“They used sound and films to great effect,” agrees Zillah Minx.

“It made such an impact,” adds Sid. “People were going, fucking hell, what the fuck? And I loved that. I loved the shock value of that.”

“When I saw them live, I became a vegetarian that night,” remembers Alice Nutter. “It was that film playing behind them. It were like a Christian conversion.”

“And I feel terrible about this, but my mum had bought me a flying jacket out of the catalogue – because I loved Julian Cope. It was really expensive, and obviously a copy, but it were leather. And I was so proud of it.

“And I wore it to the Crass gig. And I tried to leave it in the cloak room, because I was like, I can’t have a leather coat on in here. My poor mother had spent all this money and I took it home and I was like, I don’t want it anymore. I’m a vegetarian now.

“She had no idea what to do with that. My mum was picking bits of meat out of stuff and going, oh, it’s all fine. It’s fine, I’ll pick the meat out. It was an overnight conversion for me.

“But what really got me was the similarities to a Nuremburg rally. It was so similar to that Nuremburg set up with black, white and red, people standing up straight and barking at you, in uniforms – it was so strong. And attractive. I’m not saying I was a fascist, but it was just the imagery of it. It just pulled me in.

“I were like, wow! That’s what I want. I want to be in that gang! Not particularly with them – but if you remember at the time, there were thousands and thousands of us wandering round the country looking like Crass.

“You’d get off a bus somewhere and you’d just see people that just looked like Crass. They didn’t get any airplay, apart from a bit of John Peel, and yet there were thousands and thousands of us. I think it was that period when I thought, I’ve found my people.”

Matt Grimes travelled from Brighton to Digbeth Civic Hall in Birmingham to see Crass for the first time in 1981.

“It was a great gig but like a lot of Crass gigs, there was always contingent of skinheads that would turn up. It could be quite violent.”

The confusing contradictory spectacle of it all – the multimedia experience, the cups of strong tea the band shared with the audience, the Charlie Parker and Shostakovich tapes they played before the live music began, the flags and banners, the intensity, the sense of community, everyone knowing all the words – was both disorientating and seductive.

“I wouldn’t say I was suspicious, but it all made me feel a bit weird,” remembers Matt. “I’d gone to this gig and then this gig is totally not what I expected a punk rock gig to be.”

The artists supporting Crass was also important, says Matt, pinpointing people like Poison Girls who were “very much connected to that 70s counterculture. The idea of the band being very open to meeting people was unusual. I didn’t feel like I was clever enough to be able to speak to them, so I tended to avoid those situations.”

“As a 14/15 year old, I was very much going there for the music and the sense of going to something that felt important and significant.”

“At Crass gigs, I used to spend like half an hour saying goodbye to everyone,” remembers Sid Truelove. “It was just so hard to say, okay, bye, and just walk off from that unity – that love even. There were people that didn’t have any family would go there because Crass would be sitting around saying, do you want a cup of tea? Do you want a fag? Sit down, have a chat. And they’d fucking talk to you.”

Aki Nawaz thinks he first saw Crass in Halifax, but it could be Huddersfield or Rochdale or Burnley or Oldham. Either way, it was an experience.

“I liked the energy of the crowd. And I liked the anger,” he says. “But the thrashiness was a bit hard for me at that particular time. And seeing all those symbols and signs, in a way, it was a bit scary. Really strong symbols like that, they remind you of swastikas and fascism. I didn’t really know where I stood.”

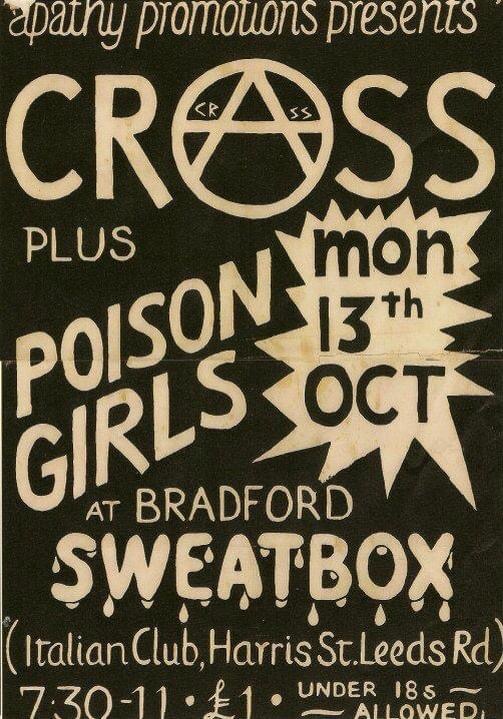

Nevertheless, Aki decided that he wanted to put them on in Bradford.

“At that time, they refused to play at normal venues, for normal promoters, and I think they were sick of all that. Or whatever reasons they had, I don’t know,” he says. “I somehow got a number and just phoned them up and they said they’d come up. I think I booked them for like 120 quid, that’s what they were charging at the time.”

“And they said, the only criteria is that you can only charge a quid in. And I said, fine. And they came up with the Poison Girls.

“The club they played at was actually an Italian community club in Bradford. It’s still there. Me and my brother, we were sticking posters up in Leeds and Halifax and Huddersfield, everywhere. We worked hard because this club was quite big, about 350-400 capacity, I think. It wasn’t even officially licensed.”

On the night, after what seems like a slightly comic interlude with Slaughter & the Dogs’ manager turning up, straight outta Wythenshawe, giving it the large one about taking the venue off him, Aki then had to deal with Crass.

“We’d got the PA system in and then they arrived,” he says. “They had like a massive following, and they gave us a guest list with like 50 names on it. And I went to them, you can’t have 50 people on the guest list.”

“And they’re like, what do you mean we can’t? We are.

“And I’m like, but you can’t. I’m sure you want to be paid at the end of the night. And they’re like, yeah, course we do. Yeah, but how am I supposed to pay you if there’s 50-odd people getting in for nowt? If I get 100 people in, what am I going to do? I’m skint. I’m signing on the dole and everything.”

Halfway through this increasingly heated discussion, Aki decided he needed to buy himself some time.

“It was getting really heavy,” he remembers. “I mean, I wasn’t a heavy guy at all. I just got really worried, like, oh no, how am I going to get the rest of the money? So I just said, I need to go to the toilet.”

“So I’m in the toilet, sat there, and I hear two people come in, and I hear them have a piss and then one of them says, have you heard about that Paki promoter? He’s making Crass pay for us to get in.”

“I fucking hated racism. The one thing I couldn’t handle in the punk movement was racism,” says Aki. “You wouldn’t think followers of Crass would come out with that stuff. I don’t know. It was just interesting.”

The fact is, Aki had been putting up with this kind of casual, matter-of-fact racism from his school days onwards, even from so-called friends. People would say this stuff to his face, never mind on the other side of a toilet stall door, and what could one kid do when faced with all that?

“The punk scene was full of it,” he says. “I would have been in a fight every night.”

“I’d heard that kind of stuff before, I just didn’t expect it at a Crass gig. They could have said, that fucking promoter, he’s a right tight get, but as soon as they dropped in the word Paki, I’m like, oh no, fucking hell.

“At that particular time, I couldn’t even speak my language properly. I was probably more English than the fucking English. But being called that kind of shit, I was like, fucking hell. I can’t get away from all this.

“That’s why I loved punk. In general, it was a tribe of people from all parts of the world and racism wasn’t really involved in it. I felt a belonging.”

Resisting the temptation to throw the pair out on their arses – probably wisely, as he was pretending to be the security for the evening and he would have had to do it himself – Aki returned to the fray and eventually managed to negotiate Crass down to just 20 people on the guest list.

“They got a bit pissed off with me,” he says. “But what happened was, it was amazing. Nobody had ever played at this place before. And it got absolutely rammed. People came from all over. I think we managed to get about 500 people in. I was kind of overwhelmed. I didn’t know what to do. It was a brilliant night.”

Dev Jonlin had travelled over from Leeds for the gig. He remembers being greeted by people distributing leaflets – “just like being given a hymn sheet when entering church”.

“The atmosphere was heavy and dark. Everyone was dressed in black and the stage was littered with banners, TV screens and projectors. I remember Poison Girls coming and going without too much fuss. And then, after a while, films were projected onto the stage with some audio in the speakers, talking about bombs and stuff, I imagine.

‘The anticipation was incredible and the crowd was rammed up front as Crass took to the stage. The next hour or so was unbelievable. It was a total bombardment of all the senses – the band on stage, the films being projected, backing tapes of voices and as one, the sweaty crowd responding to various songs.

“It was thrilling and mesmerising to witness and be part of. The power and the energy in the room was off the scale. It wasn’t like bands on stage that I’d previously seen, It really felt like the high priests and priestesses were in town and their faithful disciples had come to celebrate and pay homage.

“Afterwards, lots of folk loitered around chatting with various band members – like the priest saying farewell to his congregation after mass.

“It was,” says Dev, “an incredible night – and my initiation into the cult of Crass.”

Not a little freaked out by the whole experience of the gig, Aki left it to his brother to settle up with the bands.

“I wasn’t really a businessman, and I felt that they might take the piss. I’d got a bit scared after the interaction about the guest list. I was still young. My brother’s only a year older but he’s a bit more mature than me. I think he gave them 150 quid and they were all happy with it. I think I got about 300 quid, which paid for the posters and the rent of the hall.”

“And then I just went off in the morning and bought myself a drum kit.”

REPETITION REPETITION REPETITION

A FEW YEARS before he started Crass with Steve Ignorant, Penny Rimbaud and John Loder were in an experimental performance art group named Exit. They used a Putney VCS3 synth, which, in the early 70s, says Penny, was “a very rare object. It didn’t have a keyboard, you had to put these little pegs in. It was very strange.”

A few years later, prices for Korg and ARP synths had dropped to the price of guitars. Plenty of bands on the Crass label are using synths and drum machines – usually but not exclusively alongside guitars – but nobody became the anarcho Kraftwerk. Or even the anarcho Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark.

The Mob, Flux, the Snipers, Lack of Knowledge and the Poison Girls all to a greater or lesser extent incorporated synthesisers into their music – some of which may have been added by Penny Rimbaud and John Loder without the bands knowing anything about it until they heard the finished record.

On the Bullshit Detector compilations, generally using either synths or drum machines – only Attrition seem to have used them both at the same time – bands like Youth in Asia, APF Brigade, Avert Aversion and the excellently named Dandruff (who sound a little bit like a more strident Young Marble Giants), seem to have arrived at the party already fully onboard with the electronic revolution.

Even Boffo’s low-fi takedown of Garageland is built around the sound of a borrowed drum machine, a Boss Dr Rhythm DR55.

But synths and drum machines were rarely front and centre of the sound of the bands who released singles on Crass Records.

The main exponent of the new technology revolutionising music production in the early 80s, at least as far as the label was concerned, was Belfast-based Hit Parade Dave.

His 1982 single Bad News looked at the conflict in Northern Ireland via the medium of giddily expressive and uncompromising synth-based diatribes (“We watch the TV every night. Jesus! What a load of shite!”).

As usual, the sleeve for Bad News was packed full of context and background information, this time about the H Block hunger strikes, the British Army’s indiscriminate use of rubber bullets, the state’s use of non-jury Diplock courts to imprison people as quickly and efficiently as possible – and how media coverage of all this served to distort rather than reflect reality.

Uniquely, Crass printed up a communique to accompany the record, clarifying their position that “our concern for the H Block prisoners is humanitarian and not sectarian”.

While he’s been a fan of obscure electronic music since the 1970s, Dave, who has namechecked John Cage and Karl Heinz Stockhausen as influences in the past, was actually using the same equipment as people like the Human League or Georgio Moroder – and as a result, disconcertingly given the subject matter, often used similar sounds.

“Stockhausen and all the rest, I think I’d take that with a pinch of salt,” he says, disarmingly. “Obviously, I did like electronic music going way back to the 70s, but I also love rap music – I love rhythm.”

“Inevitably, if you were using synthesisers at that time, they’re the sounds you come up with. That definitely happened – but I always tried to make an effort to make different sounds.”

Predating the now-widespread solo producer model by a good few years, Bad News was very much a one-man band, although it seems this was more by accident than design:

“The type of politics I had, especially here, I didn’t believe that anyone would ever want to make music with the type of lyrics I was doing. So my only alternative was to do the whole production myself. And I was always intrigued by synthesisers, so that was why I did it on my own. I would have loved to have done it with a band but I couldn’t get anybody.”

“The challenge I set myself – and I don’t know if I did it – was that the music would somehow reflect the politics of what I was singing about. So I tried to create the kind of atmosphere and rhythms, offbeat rhythms and so on, that would be part of the presentation of the politics.”

Dave was “pretty poor and couldn’t afford what they called the polyphonic synthesisers – the Yamaha DX7, which, to me was the Rolls Royce. They were absolutely gorgeous. They cost about a thousand pounds.”

“So all I could afford to buy were what they called monosynths. You could buy a mono Wasp synth and then couple it with another one and then you buy the sequencer, and you could build up this kind of polyphonic sound very cheaply. I think they were about £100.

“The technology began to evolve and became less expensive. There were a few things on the horizon which really liberated me in terms of structure and sound and so on.”

“There was this thing called the [Roland TB303] Bass Line – people still use it now – and the [Roland TR606] Drumatix, and you could ally those two things together and they would keep in rhythm with each other. You could use a click track and therefore you could put the synth in with the bass and the drums, and that was how I would structure tracks.

“I thought it was absolute genius being able to construct patterns and join them all up. What happened in the studio was that everything sounded a bit weedy, but because it was all synched, it was easy enough to replace the bass drum or the snare drum with really expensive drums or whatever. The songs ended up sounding very lush, but certainly the stuff I presented was pretty basic.”

There are bits where Eve Libertine sings backing vocals, and it sounds genuinely poppy.

“I certainly didn’t think of it like that,” says Dave with a laugh. “And don’t forget, whenever I went into the studio I had the kind of very basic structure of instrumentation. But inevitably, Penny would orchestrate it a bit more – and made it a lot slicker. Which is fine, some of the orchestration on it, I absolutely adore it, but I did decide that the next album I did, I would produce myself.”

Talking of which, some of the music on the Nick Nack Paddy Wack album sounds a bit like Italo disco, sort of spacey, synth slow-mo disco – except it’s got this furious Irishman shouting over the top of it. Were you aware of any of that Italo stuff?

“I can’t say I ever listened to any. The problem was that the music I was making, it didn’t have the traditional verse chorus verse thing. Maybe a couple of songs were a bit like that, but mostly I disregarded all that. Repetition was much more important to me and I couldn’t hear anyone else doing that.

“Some people did use the same sounds and the same instrumentation but they didn’t chop up things, and have patterns that never repeated. I’d just bang it all together and hope that I’d got something.”

Listening to his stuff now, you’re struck by just how much it sounds like the Sleaford Mods.

Although Dave later became a fan, it’s difficult to believe that tracks like Here’s What You Find in Any Prison didn’t draw some influence from hip hop.

“That’s not rap, as far as I know,” he says. “I would just talk over a track and gradually it would evolve into a song.”

“But I think the Roland TR808 and the 606 played a big role in the democratisation of music. It was really compact, and it had a nice sound, but what it was brilliant at – and I thought, this is going to change everything, and it did – the bass drum went boom.

“I think the rappers were the first people to realise that you could make some really interesting rhythms with this fantastic drum machine. It was a revolutionary piece of equipment.”

Penny Rimbaud’s pre-Crass group Exit had made tape loops by sticking long runs of tape together, literally with sellotape, and running it through an old tape machine. A few years later, the Crass take on Musique Concrète found them sampling source material as diverse as Revolution 1 by the Beatles and La Marseilles on Bloody Revolutions.

The Bullshit Detectors brought us any number of unhinged tape manipulation experiments (or maybe they’re just playing records at the wrong speed) from the likes of Andy T, Waiting for Bardot and Funky Rayguns.

On their 1982 Topics For Discussion demo, the Apostles used sound collages lovingly prepared by Ian Slaughter, of Pigs for Slaughter and Autonomy Centre infamy, who went on to become a sound recordist and archivist of some note, founding the London Sound Survey amongst many other notable achievements.

Chumbawamba got to work with a borrowed Tascam four-track recorder, drawing inspiration from various sources.

Boff mentions the Last Poets, Revolution Number 9, David Byrne and Brian Eno’s My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, the Liverpool Scene (“they made an album where one side was a travelogue of visiting the States, it used samples of ads and speeches”), and Slush by the Bonzo Dog Doodah Band.

The latter , says Boff, is “a piece of haunting keyboard music overlaid with a single laugh, repeated over and over again. It’s the track I want played at my funeral.”

“We had cassettes and we’d play them by hand into a track, winding onto the next bit and playing that same bit again, and repeating,” says Boffo. “It was really hit and miss. We had one early on about the miners’ strike, which was a cut up of Margaret Thatcher speaking at the Tory party conference.”

So basically, you could have been Cassetteboy 40 years early?

“Looking back on it now, you think, oh that was us sampling but we did it with a tape recorder next to a microphone and going are we ready? It’s coming up to the beat. Press it .. now! The Tascam Portastudio, if you turned the cassette over, it played backwards. This was a revelation because then you could record drums and flip them round.”

Inspired by the sound collages of Crass, as well as the work of people like Throbbing Gristle, who just lived down the road from them in East London, and the strange, random mixtapes of their friend Richard Heslop, Sid Truelove began using a Sharp SS55 double cassette player to piece together intro tapes for Rubella Ballet gigs.

These tapes, it seems, were just Sid “messing about mixing samples from recordings of the TV and the radio and splicing the tapes. Putting them back together again and then running and recording that, putting that through a Wenn copycat and then spin that back again. I used to play that at the beginning of the gigs and people were like, what the fuck? It had bits of Batman with loads of echo on it, stuff like that.”

“And then we’d pipe in some weird Arabian FM radio channel – woooosh – and put it through the copycat. Oh my god!”

Annie Bandez, working with Penny Rimbaud, was all over this from the outset, sampling, looping and cutting up her source material, and combining that with her own uniquely visceral verse to produce very unsettling vignettes of fear and loathing on her debut single for the label, Barbed Wire Halo.

Annie’s family lived above her dad’s print shop in New York and she grew up hearing the sound of the presses throughout his working day. Later, travelling around the city, she would write to the shake, rattle and roll of rickety old subway trains.

Repetition was the starting point:

“And then I would hear melodies within that. I still do,” says Annie from her home in Miami. “My reference points were old blues and soul.”

“When I went to England, I really thought I was working on disco stuff,” she adds, implausibly. “When me and Pen were making that first single, we thought what we were making was disco. Seriously, we thought we had a top 40 hit on our hands”.

Annie was singing for a band called the Asexuals when she met Crass visual artist Gee Vaucher when Gee was working as an illustrator in New York in 1977. Crass played a few gigs in the city a year later.

“I grew up on the cusp of everything,” says Annie. “Everybody was dead, all the big rock acts, they’re all dead, aw you missed it, you missed this, you missed that, that was all I used to hear. That was what was great with punk, it was like a fuck you to these people, that pomposity.”

“I remember going to Philadelphia when I was about 17 to see the Stones. I used to like them. Me and my friend had like dyed blue hair, whatever the fuck.

“First, we’re getting abused by the audience, who were all like these fucking cracker rockers, and then the fucking Stones turned up nine hours late, it was 90 degrees and we’re wearing vinyl, like idiots. We were kids. And I remember seeing Jerry Hall, with Jagger, getting out of a fucking helicopter drinking champagne, while people were like passing out from the heat.

“And it was like a major fuck you moment.”

Annie ended up accompanying Crass when they returned to the UK. Was it a big culture shock?

“I guess the biggest difference between New York and the UK at the time was that New York was broke. You could live there for almost nothing because nobody wanted to be there. It was pretty hairy.“

“Punk there was like the old meaning of punk, just being a delinquent, being a rebel. Whereas in the UK everything’s got political connotations. I had to learn new words – I’d never heard the word anarchy before.

“I kinda related to it in that I was always just doing my thing, trying to kick, as one does, against the status quo.”

But you didn’t give it a name?

“Right. I didn’t give it a name. I was just in trouble all the time. I was always getting kicked out of classes and stuff. But I didn’t know much about the UK at all until I got there, about the classes, the royal thing, which always seemed just absurd, Northern Ireland, colonialism.”

“I was just a kid. I don’t think I ever cracked open a book until I got to the UK. I really didn’t know what people were talking about.”

THIS IS RADIO CLASH

“I NEVER really wanted people to dance to it,” says Dave Bad News of the music he made for the Crass label. “I remember I was in Soho once, and I was passing this strip club, and I was hearing this music – I think it was Rod Stewart singing – but I thought to myself, I do not want the music to be separate from what I’m saying.”

“I was very into the idea that you couldn’t digest the music without somehow listening to what I was singing about.”

Crass, the bands on their label and the associated scene didn’t operate in a vacuum but while much of the time they seemed to be studiously ignoring – or actively opposed to – the possibilities of making music aimed at the dancefloor, other punk and new wave bands around at the same time thought very differently.

Early adopters such as Kraftwerk, Can and Cabaret Voltaire had shown us the way by adapting – and even originating – the technology of the time to create, respectively, an icily austere Teutonic take on Motown, organic, improvised and cut-up ethno-jazz, and a weird, JG Ballard-suffused kind of northern soul – much of which was very firmly aimed at the dancefloor.

The UK’s colonial legacy, and the influx of people from the Commonwealth that began in the early 1950s, has long exerted a strong influence in food, fashion, literature, language and music – and for that we should be truly grateful.

It’s no bed of roses in the UK at the moment, but just imagine how shit this country would be if it hadn’t been revitalised by the fresh ideas and new flavours that people brought with them from the Caribbean, Africa, Pakistan and Bangladesh – never mind the people who’ve come here since. It doesn’t bear thinking about.

The British working classes have always been very comfortable with Jamaican music, for example, right from the bluebeat and ska days through to the glory days of reggae in the late 70s.

Thanks to the sterling efforts of people like John Peel, BBC Radio Lancashire DJ Steve Barker and Don Letts, who was the resident DJ at the Roxy when punk first began to manifest itself in London in the mid 70s, an appreciation of reggae and dub quickly became an accepted part of punk rock culture.

Songs like Germ-Free Adolescents by X-Ray Spex, Offshore Banking Business by the Members and Jah War by the Ruts make this influence clear. The Clash covered Police & Thieves and released extended versions of Armagiddeon Time on 10-inch dubplate, while the Slits produced their best work when they were working with Dennis Bovell – and then PiL released Metal Box and changed everything forever.

At the same time as all that was going on, Martin Hannett was busily soundtracking the future at Strawberry Studios in Stockport, using back-engineered Roswell technology supplied by AMS Neve and a veritable pharmacopia of drugs, to poke, prod and provoke bands like Joy Division, A Certain Ratio, ESG and Portion Control towards the dancefloor, whether they wanted it or not.

Bands as diverse as Wire, the Gang of Four, Killing Joke, the Au Pairs, Basement 5 and Urban Shakedown, the Raincoats and the Pop Group were, to varying degrees, all about a beautiful collision between the groove and rhythms of reggae/dub and funk and the energy of punk.

Talking Heads, Liquid Liquid and Material were doing similar things in New York. The Electrifying Mojo, doyen of the Midnight Funk Association, mixed up every kind of music under the sun – well, funk, new wave and electronic at least – over the radio airwaves in Detroit from 1977 onwards, inspiring young local talents such as Juan Atkins, Derrick May and Kevin Saunderson along the way.

2Tone was a wonderful flowering of multicultural creativity and positivity in the face of unrelenting adversity and shite, fusing the sound of JA ska and British punk – and (like hardcore and then jungle a decade or so later) it couldn’t have happened anywhere else in the world apart from England at that exact moment in time.

And yet again, this was music for the dancefloor.

By 1980, when the Clash released their Sandanista album, The Magnificent Seven single was supposedly the first hip hop track recorded by a rock band – although it was when Blondie released Rapture six months later that most of the world got introduced to hip hop and these ideas really began to seep into the mainstream.

A year later, This is Radio Clash appropriated the bleep-heavy stylings of electro and added a shitload of echo and delay, soundsystem-style, to devastating effect. While it was absolutely on the musical cutting edge, This is Radio Clash didn’t have much in the way of politically meaningful lyrical content – but that didn’t seem to matter at the time.

Similarly, when Brian Eno and David Byrne released their seminal sample-based, dancefloor-orientated indigenous funk opus, My Life in the Bush of Ghosts the same year, it became apparent that vocals could act as merely one element in a greater whole. It signposted the way to a different type of clarity, but hardly anyone took any notice at the time.

Even John Lydon, pretty much a spent force artistically by 1984 (don’t @ me), eventually got in on the act and, due in large part to the contribution of Afrika Bambaataa (see above), produced one of the finest moments of his career with World Destruction.

The point is, punks and like-minded people doing dance music was not unusual at any point during the seven years in which Crass operated.

Obviously, there is a tension between the requirements of the groove for uncluttered time and space, and the desire to make a coherent political point – but most of the 2Tone bands seemed to manage it.

The Au Pairs, Gang of Four and the Pop Group did too.

How brilliant would it have been if Crass had tried to do the same thing?

There were plenty of people on the scene who already knew about life on the dancefloor, after all.

While Annie Bandez loved the energy of New York’s burgeoning punk scene towards the end of the 70s, disco was, she says, “much more important.”

“It was a cultural revolution, in a real way, because it brought together black and white and latino and gay and straight, y’know, it was the first time that had happened and it was pretty revolutionary.”

The big cultural touchstone for disco in NYC in the 70s is the supposedly iconic Studio 54 – where, let’s not forget, Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards couldn’t even get through the door when Chic’s music was being played inside, inspiring them to write a song called Fuck Off. They later changed its name.

Wasn’t that place all about the velvet rope?

“I went to all of those places and got kicked out of every one of them,” says Annie. “I went to the opening of Studio 54 with my friend Bobby. He lied and said he was writing a book – he was no writer. I thought, well, they’ve got nice flowers. I was impressed.”

“But I’d been sneaking into clubs since I was 14, mainly gay men’s clubs, where that music was busted out before anywhere else. I’d go along for the ride. It was downtown. First place I went, it took me weeks to realise it was all men.”

Aki Nawaz says that, besides hearing the Clash and seeing the Sex Pistols, 1977 was also an important year for him because that was the year he sneaked into the ABC in Bradford with a mate to see the X-certificate Saturday Night Fever.

“I was contemplating the John Travolta look,” he says. “I was quite tempted. I quite liked all that disco stuff.”

While my man could definitely rock Travolta’s trademark white suit, unfortunately, this vision in crimplene was not to be.

“I was a secret disco lover. I always used to listen to disco before I went out, Diana Ross, Saturday Night Fever, put the vinyl on, get in the mood, and then go out to a punk gig. I always loved disco. I think most punks loved disco but they didn’t want to admit it. It was supposed to be the thing that we hated.”

“I didn’t really like disco, to be honest with you,” says Paul Hartnoll, although at this point he was too young for anything but village hall discos. “To this day, I still don’t really. I appreciate some of it. I like Sister Sledge. A bit. But I don’t actually own any disco records.”

Meanwhile, in Scotland, a young Stirling resident by the name of Chris Low first heard punk via John Peel. Although his first big gig was Sham 69 at Glasgow Apollo, other influences were at play.

Chris’s love of punk rock was matched only by his love of disco – although you probably wouldn’t get this from listening to the bands (including Political Asylum, the Apostles, Oi Polloi and Part 1) he’s played in since.

“The house I grew up in overlooked a discotheque, the only discotheque in the Bridge of Allan,” explains Chris. “1976, 1977 was when I really became conscious of music, so basically, every night, I would just sit and look out of the window and listen to music from this club.”

“I remember really being hit by stuff like I Feel Love, but at the same time, I was also really struck by the first punk records I heard on the radio.

“So I’ve always kinda been into dance music.”

Having had a thorough grounding in anarcho punk theory by interviewing bands like Crass and Discharge for his fanzine Guilty of What, Chris joined the Apostles at the age of 14 and began to get more practical experience.

He’d bunk the train, spend the weekend in London, and then go back up to Stirling for school on Monday morning. As often as not, he’d be carrying fresh new electro from London’s record shops.

“I remember going down to stay with the Apostles to go to record the third Apostles record and I bought the Mob album and the 12-inch Shep Pettibone mix of Madonna Lucky Star – and everyone was like, what the fuck is that? It’s fucking brilliant!”

“I was bang into disco, underground disco, and mainstream soul,” says Choci.

“I was brought up as a kid on Motown and Philly soul. My mum and dad would get drunk on a Sunday afternoon and the music would be on dead loud. I was open-minded about music, although it wasn’t deemed cool to be into disco when you had like a green mohican. I was a closet disco fan.”

But, in late 70s/early 80s Britain, there was more to dance music than disco, particularly in the Midlands and north of England.

Alice Nutter had been going to northern soul all-nighters around the north west since age of 14 (quite a pivotal age in the 70s, it seems).

“I used to practise dancing all week. I used to spin and do all that stuff,” she tells me over the phone as he takes the bins out.

“Dancing to northern was all about free expression. You had to be in tune with your body to dance like that. It wasn’t all the same steps that you did. You knew the steps, but you put things together that reflected how you felt about certain sections of songs, and you made that up as you went along.”

Two or three years in, however, Alice had begun to tire of some of the attitudes she encountered on the northern scene. It was, essentially, a working class movement and working class people in the UK at the end of the 70s were not necessarily a particularly enlightened group of people.

Then again, neither was anyone else.

“Basically, the northern crowd, when they weren’t on drugs, they were quite reactionary,” Alice remembers. “Not everybody. But I remember sitting in pubs after being up all night and talking about music and people were like, you’ve got the wrong haircut, love.”

“The men collected records and the women trailed after them. I didn’t have words for it and I didn’t realise I was rebelling against it, but I never wanted to do it. I never wanted a steady boyfriend. Y’know, I’d sleep with somebody and then not want to carry on seeing them. In northern circles it were a bit like, but no, we’re supposed to get engaged.

“So when punk rock came along, I didn’t fully understand it. I can’t pretend I heard it and thought, I’ve found my people, but I did think I’d found a bit of that thing I was looking for where you don’t have to be somebody’s girlfriend.

“I didn’t have a word for feminism but I were looking for it,” decides Alice. “I got the bus to Manchester on my own to go to a bookshop and look for stuff about girls and women because there were nowt in Burnley – you had to make a conscious effort to try and find stuff.”

“What got on my nerves about northern is that you were expected to settle down and be somebody’s girlfriend. And I never did. I was as wild as the blokes and that weren’t really acceptable.”

Did you carry on dancing once you got into punk?

“There were always discos in Burnley that would play Being Boiled by the Human League and all that sort of stuff. So you could actually go and dance to quite decent records.”

“But at gigs, when everyone started pogoing, it weren’t really me. I mean, I followed Adam and the Ants on a whole tour, in like 1979 or 1980.

“And then I got into that Ant dance thing.

“But it was never the same as when you danced to northern. I mean, you had a routine, you’d have to really know your steps and know what you were doing. And just let rip and let go. Punk dancing were never like that.

“I have to say, the dancing in northern was absolute freedom. Because you had a lot of space as well. People don’t think about this when you go to discos now, but when you went to an all-nighter, you would mark your space out by dancing in a certain bit of the floor – and everyone would leave you that space for you to do your thing in.”

Sid Truelove grew up in the Midlands, also in thrall to northern soul – he was a regular at Wigan Casino – before moving to London to work as chef just as the initial punk explosion began. Meanwhile, Zillah says she was “a 75/76 punk. I saw the Sex Pistols before they were on TV.”

Rubella Ballet were pretty much the only people from the extended Crass family who were flying the flag for the dancefloor throughout this whole period.

Rubella’s debut live appearance came after Crass asked the audience at a Conway Hall gig if they’d like to use their instruments, and the initial line-up included Vi Subversa’s kids Gem Stone and Pete Fender, as well as Annie Bandez. They played loads of gigs with Crass, the Poison Girls and Flux of Pink Indians, for whom Sid also drummed.

Basically, Rubella Ballet were about as anarcho punk as you could get without releasing a record on the label. Or wearing black clothes.

Sid was also big into Adam and the Ants back in the day.

“Those two drummers, you know – chunka-chunka-chunka – that was really dancey and tribal,” he says. “And I think I took that tribal feel into Rubella Ballet and Flux.”

“Like, someone like Discharge was all hi-hats and snare. I heard the two drummers really early, when they were just called the Ants, and it was a stunning sound. I mean, what a sound. So I thought if you could hit the drums twice as hard as you’re supposed to hit them, you could create that kind of sound.

“I just put a bit of expression into it. I was a really good friend of Lance de Boyle – Gary from the Poison Girls – he’d have videos of Burundi drummers and stuff like that. That’s how I started drumming, because he let me use his drum kit in the rehearsal studio at the Poison Girls house in Epping.”

Right from their very first release, the Ballet Bag cassette in 1981, however, it was clear that Rubella Ballet were willing to engage with new ideas in an attempt to do something different – in a scene that could sometimes seem disinterested in musical innovation.

When they recorded the tracks for Ballet Bag, Sid says, the music they were listening to was “Grandmaster Flash, all the time. And dub. Anything that was completely bonkers.”

Krak Trak and Blues were very raw and basic funk tracks that weren’t a million miles away from what ESG were doing in Brooklyn at more or less the same time. No really.

But blues as in blues dances or blues as in pills? Or just the blues?

When they first jammed Blues, Zillah remembers they thought it sounded like a blues song, but “it also reminded us of blues speed and blues party. Later, it morphed into Death Train about the trains taking the Jewish people to camps, and the blues idea of drug use being a train ride to death.“

Crikey.

With bands members coming and going on a fairly regular basis, says Zillah, developing ideas that they had jammed into finished songs was often “a long, weird drawn-out process.”

“I think we always wanted to do something different but it didn’t always come across as well as we wanted it to,” she says.

A few years later, when the pair were living in a tower block with thin walls and lots of neighbours, Sid found himself unable to practice his beloved drums.

“I couldn’t use the drum kit in there because everyone would go nuts, so it was about doing anything musical I could with the headphones on,” he remembers. “I even went crazy and bought like a midi keyboard in 1981, which was loads of money and it probably had about eight sounds.”

“It had a sequencer on it, and you could have 16 bars and eight channels, but then you had to do live mixing. You had eight channels and you could just fuck around with that. I used to drink Special Brew, and I smoked hash at the time, and I would do that all night.”

If Sid and Zillah did not exist, we would have to invent them.

THE KIDS WERE JUST CRASS

CRASS were a response – outrage, anger, disgust – to the absolute insanity of the doctrine of mutually assured destruction during what turned out to be the last days of the supposed ‘cold war’.

Thatcher agreed to host US cruise missiles, a so-called first-strike weapon, despite having no control over their use. The missiles were sited at USAAF/RAF bases across the UK, effectively making the entire country a target.

Peace camps, including exclusively female protests, sprang up around Greenham Common airbase, the Menwith Hill and Fylingdales listening bases, and the Faslane naval base that housed the UK’s supposed independent nuclear deterrent, Trident.

The people at these protest weren’t any kind of extremists – a good number of them were actually Quakers – but a truly extreme and reactionary government had put them into a position where they felt they had no choice but to do something. It was a very polarising time.

Alice Nutter first saw Crass play live just as she was in the process of joining the gang that was Chumbawamba. While never exactly slavish followers of Crass, it’s probably fair to say the Southview House lot took a good deal of inspiration from the ideas and methods that came out of Dial House.

“They lived in a commune, so we looked at them and thought, right, we’ll get a commune. And we did. You know, we shared our money for a lot of years. They started us off,” she remembers.

“And it was like, right, we’re a group, we can change the world, we can do this, we can do that. It was a different set of people to what I was used to. They were really creative, and I think that’s what I’d been looking for. Because I’ve always been quite a creative person. Not musical, but creative.

“Eventually we morphed out of replicas of them into a version of ourselves. But I thought that scene was really powerful. Suddenly, you had a group of people who were linked by this musical movement, and we hadn’t quite worked things out, but all those Stop the Citys and demos, you go and you’d see the same people, who were on the move the whole time.

“I thought it was an amazing thing. It had somehow moved beyond rhetoric. And I somehow belonged to this group of people. We didn’t even have to know each other to be part of this revolutionary underground. That felt amazing.

“And also, it looked pretty cool when you had hundreds of people wandering around in black rags. It just did.”

Choci saw Crass, the Poison Girls and the Fatal Microbes in early 1979 at the Sea Cadets Hall in Cambridge, at a gig promoted by his mate.

“It was raucous. And very raw. It just seemed like a bunch of mates having a laugh,” he says.

There was lots of pogoing and spitting. And lots of sniffing glue.

What did you make of the presentation of the gig? The films and sound collages, the banners, all them geezers dressed in black?

“What they were saying, it just felt right to me,” says Choci.

“Punk was going in different directions,” he explains. “There was new romantics, there was the goth thing, and then you had the really heavy stuff like Discharge and the Exploited. To me, it just felt like Crass were on point. I definitely wasn’t going down the new romantic road, for sure.”

Rather than the Damascene conversion experienced by many people seeing or hearing Crass for the first time, Choci says that, for him, their influence was a little more subtle.

“I was kind of leaning that way already, that kind of Fight War not Wars ideology. I was starting to hang out with feminist women, so all that shaved women, screaming babies stuff seemed on point. It seemed like an evolution of the suffragettes, this is women taking a stand against the patriarchy.”

“So it wasn’t something that changed my life because I was already going in that direction – but it just confirmed I was going in the right direction. There were other people feeling the same.”

Although he never got to see Crass live, listening to them and the other bands on the label had a profound effect on Paul Hartnoll in the early 80s.

“There was an element of it that was like, oh, you’re saying what I think, that’s amazing. That you can be yourself, that you don’t have to follow the crowd, and don’t piss on anyone else’s bonfire. I was like, yeah, that’s exactly the way I feel.”

Paul says that two records in particular taught him some “massive lessons”.

“It was mostly Flux and their song Sick Butchers that got me into vegetarianism,“ he remembers. “But the biggest eye opener – and I think the hardest lesson to learn, coming from Dunton Green, a Kentish village attached to a market town – was when I got the Penis Envy album and got informed and schooled about feminism.”

“It took me years for me to fully take it all in. Have you ever see dogs looking at something that’s weird and they can’t quite understand it and they’re turning their heads to one side? That was me.

“Oh women are equal? Yeah, I kind of knew that. But hang on a minute, surely they’ve still got to do the cooking and cleaning? The men have to go to work. That’s all I see around me. What?”

Though he couldn’t really put it into practice, what with him being 15 and living in Dunton Green, “the stuff on Penis Envy really rang true with me. I understood it. I was like, fucking hell. This is mental. We’re all doing it wrong. It blew my head off.”

Paul bought everything he could on the label.

“I had a real lucky break. I went to the Spinning Disc, a local record shop in Sevenoaks after school one day. They had a secondhand singles section and someone had offloaded a load of Crass label seven-inches. I just bought the whole lot. There are a few missing – I didn’t get Honey Bane or Captain Sensible but I think I’ve got pretty much everything else.

“And when I went to London, I just used to collect anything on the Crass label. And Corpus Christi. And I followed the bands off into their own little directions, like Omega Tribe.

“And another huge band for me were Rudimentary Peni. Fucking hell! Those first two EPs, especially the second one with The Gardener on it.”

“I was so waiting for the album,” adds Paul, “and it didn’t disappoint. But they weren’t anything like Crass. It was sort of experimental punk music. They were really out there, musically.”

Stephen Spencer-Fleet, having bought Feeding of the 5000 and Stations of the Crass, listened to them “again and again and again” at home in Swindon.

He became a regular at the Freedom bookshop, the Wapping Anarchy Centre and Centro Iberico, and hung around Hackney with the likes of Genesis P Orridge and the Hackney Hell Crew. Stephen attended the Zig Zag squat gig and was also one of the regional coordinators for Stop the City in late 1982 and early 1983.

As well as all that, Stephen and his band Disturbance From Fear organised gigs in Swindon with bands like the Snipers, Subhumans, Flowers in the Dustbin, Shrapnel and Lifecycle.

One gig at the disused slaughterhouse known as the Bacon Factory, says Stephen, featured an all-star line up that included “the Chumbas and Passion Killers, Sanction from Exeter, with Rich Cross who now does The Hippies Now Wear Black, and Smart Pils, who wrote a song about the experience.”

“In the early 80s, there was an existing uniform. Form a band, do a zine, dress in black, follow these bands around, squat. And I won’t lie, I’ve done most of these things,” says Stephen. “I think it’s about finding a route out of that in a way, to take on board other sorts of influences.”

“Crass were hugely influential and opened up a whole set of ideas that were then manifested by other anarcho punk bands,” says Matt Grimes. “I was really into the scene, really into the ideology, the politics. I went to the Stop the Citys, I joined Class War, I became a vegetarian and then a vegan.”

“I didn’t go for the whole wearing plimsolls and rolled up black trousers, I still maintained my leather jacket. But I used to go hunt sabbing on the back of all this.”

“I just became a Crass head completely,” says Chris Liberator. “I got involved in the anarcho scene and really got to respect Crass. They really did rock people’s worlds. It was hardcore political statements that had never really been heard by people before, in a really direct style.”

Chris grew up in Hornchurch in Essex and his first band, Cold War, did a gig with the Apostles and the Sinyx in Southend. They got chatting to the Apostles on the train home.

“They told us about this thing they were helping to set up with the money from Bloody Revolutions down in Wapping. On Sundays, we’re going to go down to this warehouse, get it cleared out and set up.”

“So we got involved with it and ended up playing the first gig at the Anarchy Centre and then obviously, that became really big and an epicenter for the scene in London. And that’s how I met the other Hags.”

It turns out I have been mispronouncing Hagar the Womb for the best part of 40 years.

When Aki Nawaz used the money he made from his Crass gig to finally replace his crappy drum kit, he was playing in a band called Violation with two mates from the Bradford punks scene, Buzz and Barry, and a succession of not-very-good singers, including one called Oxfam Harry.